Awaab’s Law: ‘Legislation requires extra clarity, capacity and capability’

Posted on: 4 December, 2025

By James Beckwith MA, MSc, LLM, PgCAP, FRICS, FAIQS, CQS, FCIArb, FHEA

Senior Lecturer, University of the Built Environment

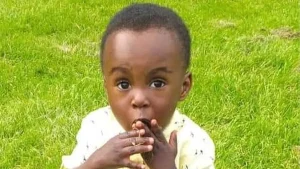

The introduction in October 2025 of Awaab’s Law marks one of the most significant shifts in social housing regulation for many years. It follows the tragic death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak in 2020 from a severe respiratory condition caused by prolonged exposure to mould.

The introduction in October 2025 of Awaab’s Law marks one of the most significant shifts in social housing regulation for many years. It follows the tragic death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak in 2020 from a severe respiratory condition caused by prolonged exposure to mould.

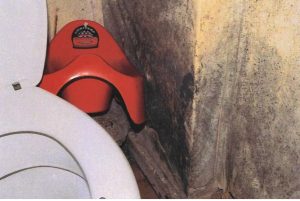

Rochdale Coroner’s Court found that the Ishak family’s one-bedroom flat was inadequately ventilated and not equipped for normal day-to-day living, and that repeated complaints had been met with the advice to ‘paint over it’.

It is appalling that it takes the death of a child to force change, and equally troubling that parts of the property and construction industry require legislation to provide safe, healthy homes. Yet the reality is that statutory reform has again been required, just as it was after Grenfell with the Building Safety Act 2022.

While the intention of the legislation is clear, its practical delivery is far more complex. It will require new skills, additional resources and far greater clarity for those responsible for implementing it.

What is Awaab’s Law?

What is Awaab’s Law?

Awaab’s Law sits within the Social Housing (Regulation) Act 2023 and is operationalised through the Hazards in Social Housing (Prescribed Requirements) (England) Regulations 2025.

These Regulations imply a contractual duty in all social housing tenancy agreements, requiring landlords to meet strict timeframes for identifying and rectifying hazards.

Initially, the focus is on damp and mould and any other emergency hazards that present immediate risk. From 2026, the Regulations will expand to cover excess cold and heat, falls, structural collapse, fire and electrical hazards, hygiene, and food safety, before extending to all remaining Housing Health and Safety Rating System hazards, excluding overcrowding.

Awaab’s Law: Complexities around identifying types of hazards

The Regulations apply to almost all social housing occupied under a tenancy, and distinguish between:

- Emergency hazards: those posing an imminent and significant risk of harm.

- Significant hazards: those posing a non-imminent but still serious risk.

If a potential emergency hazard is reported, the landlord must investigate and undertake necessary safety work within 24 hours. For significant hazards, landlords have ten working days to investigate, followed by a further five working days to undertake required safety work. A written summary of findings must be provided within three working days of the investigation concluding.

If a potential emergency hazard is reported, the landlord must investigate and undertake necessary safety work within 24 hours. For significant hazards, landlords have ten working days to investigate, followed by a further five working days to undertake required safety work. A written summary of findings must be provided within three working days of the investigation concluding.

The legislation is designed to prevent the kind of delays that contributed to Awaab’s death. It places decision-making power into the hands of tenants and makes landlords legally accountable for timely action.

However, this creates complexities. Tenants are not necessarily equipped to recognise an ‘emergency hazard’. There is also a risk of both under-reporting truly dangerous conditions and over-reporting issues that do not meet the threshold.

This, in turn, creates operational pressure on social landlords, who must have suitably trained investigators available at short notice.

Awaab’s Law: The issues behind implementing the Regulations

The Regulations state that investigations must be undertaken by a “competent investigator”. However, the legislation does not define what competency actually looks like in practice. Nor does it prescribe how damp and mould should be assessed or remediated.

Currently, there is:

- No mandated survey methodology.

- No national remediation standard.

- No requirement for specific ventilation or fabric improvements.

- No technical definition of what constitutes ‘making the home safe’.

This is despite the coroner’s findings in Awaab’s case criticising inconsistent and unclear diagnostic practices across the sector.

Further, each home will require a tailored approach, from improvements to ventilation to changes in building fabric or insulation.

This places a significant resource burden on landlords because it means they must have:

- Trained investigators available around the clock.

- Contractors ready to mobilise emergency works.

- Budgets for reactive maintenance.

- Capacity to provide temporary accommodation if repairs cannot be completed in time.

This will be particularly challenging for smaller housing associations with limited finances. As a result, the sector has been calling for clarity on funding, with the Local Government Association declaring that councils will require additional support to meet these new expectations.

There is also ambiguity in the sequencing of duties. Where a significant hazard investigation uncovers an emergency hazard, the Regulations are not explicit about how the two sets of timeframes interact. Although the overarching principle is clear – emergency issues require immediate action – the procedural overlap is likely to cause confusion.

Awaab’s Law: What counts as ‘required work’?

Section 4 provides a broad definition of required work: actions needed to make the home safe and prevent recurrence of the hazard so far as possible.

The breadth of the definition reflects the variety of hazards but also leaves considerable scope for interpretation. Without national technical standards on mould remediation or ventilation performance, outcomes may vary significantly across providers.

Awaab’s Law enforcement: ‘heavily reliant’ on tenants

If a landlord fails to act, tenants may escalate their complaint to the Housing Ombudsman, who can order repairs and compensation. Failure to comply can trigger intervention from the Regulator of Social Housing, including unscheduled inspections or unlimited fines, with potential criminal prosecution for persistent breaches.

However, these pathways rely heavily on tenants taking action. Awaab’s case demonstrated that vulnerable occupants are often unable to escalate issues effectively. Regulatory enforcement is therefore reactive rather than preventative, and the system does not yet include routine inspection cycles that might identify hazards before they become dangerous.

Awaab’s Law: We need more investment in skills

Awaab’s Law represents a clear moral and professional imperative for the housing sector. It codifies what should always have been standard practice: swift investigation, open communication and timely remediation of hazards that threaten health.

However, more clarity is needed on the definitions discussed above to avoid the grey areas that can lead to life-threatening delays.

Also, investment in extra skills and resources is needed to meet the new requirements. Surveyors will need training in damp and mould diagnostics, and landlords will require experienced, rapid-response maintenance teams.

The Regulations rightly raise the bar, but the challenge now lies in ensuring that every provider has the clarity, capacity and capability to meet them. Awaab’s death revealed systemic failures, but only sustained commitment will turn preventative legislation into lasting change.

Help to make a change – learn more about the University of the Built Environment’s BSc (Hons) Building Control

What is Awaab’s Law?

What is Awaab’s Law?